On March 16, 2020, a manuscript of a science journal article appeared online from a French research group. It claimed that a clinical trial had shown that a combination of two drugs was promising in combating SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

Led by French scientist Didier Raoult, the research group from Marseille in France described the effects of the two drugs – an antimalarial named hydroxychloroquine, and an antibiotic called azithromycin.

“For ethical reasons and because our first results are so significant and evident, we decide to share our findings with the medical community, given the urgent need for an effective drug against SARS-CoV-2 in the current pandemic context,” the manuscript said.

Over the next few days, the two drugs catapulted into fame in France and globally. Hydroxychloroquine – and its older cousin, chloroquine – were heralded as hopes against the pandemic, including in France, where COVID-19 has cost more than 23,000 lives, trapped France’s residents in a lockdown for more than a month, and thrown the French economy into its worst recession since the end of World War II.

“It has become a household name here,” said Nishant Kumar, a physicist completing his PhD in Poitiers, a small city in western France, referring to hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine. “It’s everywhere on the news.”

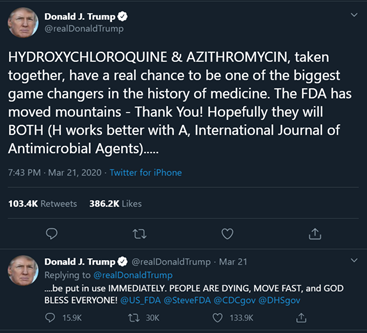

Meanwhile, Raoult’s manuscript was published in the International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents on March 20. A day later, U.S. President Donald Trump called hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin ‘game changers’ in a tweet and a press conference. He called on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as well as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to quickly allow for the drugs combination to be used to treat COVID-19 patients.

However, while Raoult’s paper had caught international attention, it had also made many in the scientific community raise eyebrows. They expressed their concerns about the study’s gaping flaws in methodology on social media as well as PubPeer, a discussion forum website commonly used by academicians.

Elisabeth Bik, a scientific consultant, was one of the first to detail such issues with the paper, both on PubPeer as well as on her own blog, Microbiom Digest. One of the main issues she brings up is a source of conflict of interest – one of the authors on the paper, J. M. Roulain, is the Editor-in-Chief of the journal in which the article was published.

“This is probably why their paper was published less than 24 hours after they sent it for review,” she guesses. Normally, science papers can take weeks or months to peer review and revise before being published.

Meanwhile, Dominique Costagliola, an HIV researcher at France’s health research institute INSERM, explains that the problems with the paper, its methods, and its results were much deeper.

Costagliola, a member of the French Academy of Sciences, points out that the paper only talks about 20 patients who had a successful recovery, without elaborating on what happened to six other patients who were also taking hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin. As it turned out, of those six people, one stopped taking the treatment to go home, one had an unexplained side effect that was strong enough to stop taking the drug, three were admitted to the ICU, and one died.

“So, does the treatment work? It doesn’t prevent you to go into reanimation [ICU] and die,” she comments. “In an appropriate analysis, you should have counted at least those four as failure. Not discounted them.”

She adds that the study looked at patients’ health after six days of taking the drugs – a meaningless comparison since many COVID-19 patients who recover tend to have improved health after six days regardless of their treatment.

Such technical as well as large-scale issues with the paper did not stop Raoult from gaining popularity. So much so that Bik, the scientific consultant, found herself a target of social media attacks.

“I get tweets everyday from French and American trolls. It’s slightly better now, but I still easily get about 10-20 tweets per day.”

Stephanie Sylland, a French tour guide and small business owner in Versailles, says the vitriol is rooted in Marseilles’ frustrations with the government and establishment. Raoult’s research group is based in Marseilles.

“Marseilles is not as privileged as Paris and Lyon. A lot of Raoult’s supporters believe the backlash against Raoult is part of the Parisian elite agenda.”

Meanwhile, Nishant Kumar, the PhD candidate, calls it a failure of science reporting.

“Science journalists were quick to latch on to the hopeful findings of the study. But they did not give us the context: what was the sample size? What were the limitations? What would have been the right way to conduct the study in normal times?”